The Biohacker's Guide to Rapid Skill Acquisition: Using Pharmacology and Neuropsychology to Build Skills

My masterpiece, my mona lisa. #2

Have you ever wondered what it would feel like to acquire skills at a rapid pace, becoming someone for whom everything just seems to click? Then this guide is specifically for you.

As someone who struggled with organizing thoughts and implementing theory throughout my life, I made it my goal and undying passion to accumulate my ideas and amass them into something special

These insights have come from 2,000 hours spent on the tatami, and thousands more spent elsewhere.

This guide is an industry-refined cookbook combined with pharmaceutical accessories to leverage in your skill acquisition journey. (I sincerely hope you enjoy)

Disclaimer: This guide is not solely aimed at jiu-jitsu; and its principles can be applied to all facets of life.

Before we start, I want to give you some background on my story, explaining why I feel I can provide you with the necessary tools to acquire skills rapidly.

As someone with a background in the sciences, although relatively new to the field of martial arts (I started competitive BJJ in late 2021), I went through a period in which I faced an unhealthily high amount of brain fog due to an unsatisfactory lifestyle

This left me unable to learn effectively and forced my hand to reverse this situation.

I had no idea where to start, but my passion for jiu-jitsu inevitably pushed me to break barriers, as I was solely determined to improve and would do anything to enhance my skills.

Please note that while this guide will provide you with everything you need to excel, implementing these strategies in a manner tailored to you is what will truly set you apart

Just as the fastest car in the world won’t perform well unless you have the right roads to drive on, these tools won’t mean much unless you integrate them into your daily routines.

So, without further ado, let’s begin.

As You Should Know, the Foundational Structure of the Learning Process Must Be Built on a Solid Base.

For me, these are principles and maxims that must be abided by. Supplements, nootropics, and other pharmacological tools are the icing on top of this cake, so to speak.

Principle Number 1: The Principle of Least Effort

Also known as the genetic law of least effort, this concept, often discussed within behavioral science, suggests that humans have a cognitive tendency to choose the path of least resistance.

Through natural means or ‘automation,’ we reduce our perceived cognitive load

Our perceived rate of exertion, as you may call it

When making decisions or performing tasks. This is often referred to as your ‘cognitive economy.’

The brain tends to minimize mental effort by relying on shortcuts or familiar solutions rather than expending extra effort on complex problem-solving, much like how, in electronics, a circuit will naturally take the route of least resistance, avoiding any obstacles that break the flow

So in short, you must learn to fall in love with the tedious.

Let’s Apply This to Human Psychology.

Say you write a 10,000-character Substack long-form post, and three people read it. Then you write a 400-character Substack note, and 80 people read it. Why? Because it’s the path of least resistance.

But why am I telling you all of this?

Here’s how this applies to rapid skill acquisition.

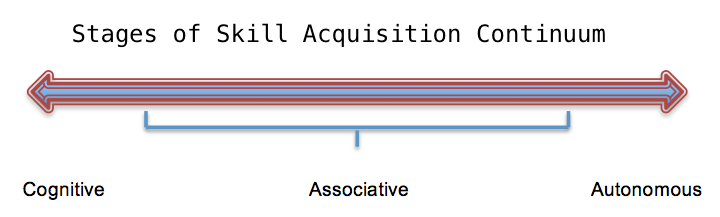

When you begin a new skill, cognitive load will be at its highest.

Consider an example: when you start to drive a car, you have ten different sub-skills to learn—shifting gears, checking mirrors, steering—and as you practice, these become automated. This is because, as soon as your brain is ready, it will pass these tasks off to automation.

It’s also important to note that over 95% of your brain is cognitively automated

(scary, I know).

This is interesting because it helps you understand that the reason you feel like your brain is fried when learning a new skill is that your cognitive economy is exerting this output.

You’re learning 8–9 different sub-skills that you haven’t encountered before, and your brain is trying to process the fresh stimuli before it can pass them off to automation.

So, next time you feel like the house of cards is going to fall down, remember that it’s just your brain trying to preserve your cognitive economy

You’re going to have to let it get into some debt, and eventually, the books will be balanced.

Principle Number 2: The Principle of Information

Not all information is created equal. Due to the overwhelming nature of the internet, we have inevitably hit a point of diminishing returns with the sheer volume of both good information and wacky gatami guards.

(Shout-out to my judo coach Colin for that phrase.)

Luckily for me, I have been blessed with amazing mentors.

My BJJ coach is a European champion at black belt level, and my judo coach is a former Olympian, so I haven’t had to scour the internet for what works due to the elite nature of my training environment. (This is Principle Number 3.)

With the nature of the internet and the increasing amount of poor information, it has become increasingly hard to find solid guidance.

This is understandable, considering most short-form content is churned-out nonsense used as engagement farming.

The only way to find valuable information is to access elite groups (shout-out to my good friend and his meticulously curated Telegram) or to search for the golden nuggets yourself. (Not everyone is willing to do this.)

The process of finding a mentor is much shorter, and a principle you should learn early is that you will need to pay for good information, or there will be some form of transactional exchange. (Shout-out to the young men reading this.)

Learn this principle early, and you’ll surpass your peers.

The reason I’m telling you all of this is that the implementation of improper information will set you back a few steps in the chain.

Imagine building muscle memory around things that don’t work.

This will take double the time to reverse. (I learned this the hard way)

Don’t make the same mistakes as me.

Principle Number 3: The Principle of Environment

Let’s revisit school for a moment with the sunflower experiment: remember in kindergarten/primary school when everyone was given sunflower seeds, some water, a little sunshine, and good vibes?

Twenty children ten of them grow flourishing sunflowers, while the other ten get nothing but a floppy sunflower

What determines the fate of the sunflower?

Environment

The children who understood soil, water, and sunlight will inevitably face the end result of a beautiful yellow sunflower, while those who neglected the concept of environment will face a dead, floppy sunflower

Even though they understood the theory of how to grow it, they didn’t incorporate an environment that supported its growth.

I learned this at 17 when I volunteered to grow flowers

My mentor taught me that even flowers can survive harsh winters if placed with a protective sheath to facilitate their growth.

Why am I telling you all this?

It’s simple: you know what you must do. It’s not knowing that’s the problem, it’s doing, and creating an environment that supports and facilitates that growth

What’s your protective sheath? When do you work best? What times of the day create undying attention? What detracts from that attention?

These are all key indicators that need to be identified EARLY.

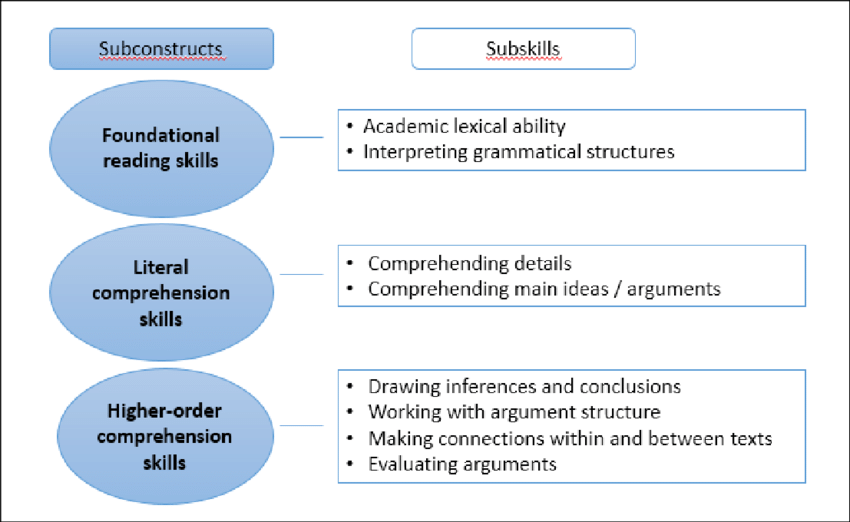

Principle Number 4: Sub-skills

When acquiring skills in any facet of life, you must address what makes up the ‘bulk’ of these skills.

As discussed at the beginning of the article, you may be led to believe that to get good at anything, you must simply brute-force your way to competency. While this is true to some extent, and a certain level of brute force is needed to become adequately competent in your chosen field of expertise, you must first identify the key areas you need to focus on. For me, in pharmacology, I need to address the sub-skills that make up the niche: mechanisms of action, drug interactions, etc. These are the sub-skills that constitute the bulk of the learning process.

Focus acutely on these and refine them until the day that you die.

Principle Number 5: Being Receptive

All the information in the world is useless unless you’re receptive to it and willing to implement it. If a black belt tells you something you're doing wrong and you can’t respond to authority because your ego is ten feet tall, how do you expect to improve? I'm not saying you should blindly follow someone just because they are in a place of authority, but the Dunning-Kruger effect is real. At the beginning, when you experience newbie gains, you’ll feel unstoppable—like a dog with two dicks, in the words of my Irish grandmother.

Then, all of a sudden, the newbie gains will fall off, and you’ll be faced with the pit of despair (where the real learning begins to occur).

Principle Number 6: Grit

This is something that can't be taught, unfortunately. There will be times when you’re dragged away from your skill. You might feel that you’ve finally had enough, that you’re starting to hate it because you can’t grasp certain concepts, or that you’re losing all the time. My first 17 competitive jiu-jitsu matches ended in losses; most would have quit then, but I didn’t. Unfortunately, I can't transfer this skill to you; it’s something that needs to be developed through hardships experienced. It’s easy to persevere when you’re winning, but when you’re losing, that’s when you’re really tested, and on the road to skill acquisition, the negative mind is the enemy.

Principle Number 7: Mistakes

Mistakes are a fundamental block when it comes to learning.

This is how your brain learns to interact with stimuli.

Your brain is a supercomputer that tries to understand all stimuli and paints your picture of its world model through various receptors like dopamine, serotonin, etc.

This is why everyone's perception of the world is different.

But one thing that is true for everyone is that your brain works through an input and output formula.

Each waking moment of the day, your brain is trying to work out how to interact with stimuli.

Imagine you’re training in boxing, and you get hit with a specific combination on repeat.

Eventually, your brain picks it up after a few tries. Because of this, it then makes a prediction, and it's either right or wrong.

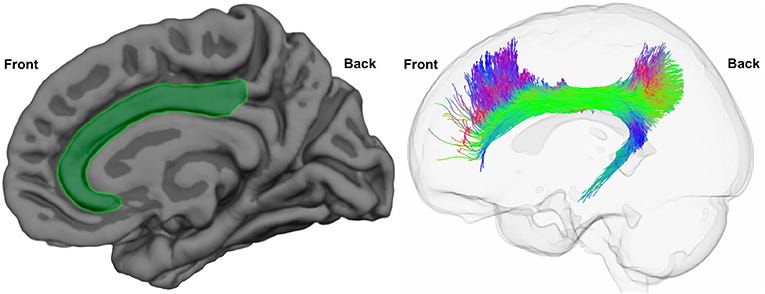

If it's wrong, the brain will hit repeat like a slot machine, and if it's right, the brain will slot this in for neuroplasticity (creating a neural pathway/muscle memory).

Your brain is constantly working off predictions. An example of this is the concave face illusion, where your brain predicts a concave face only to be met with something completely different. This is how your entire world model is built: off a series of what will happen next.

So having a negative connotation around being ‘wrong’ is, in fact, counterintuitive to your end goal.

We must accept that being wrong is the precursor to being right.

So next time you feel bad for being wrong, just accept that you’re one step away from setting neuroplasticity and gaining a thorough understanding of your new world model.

Now that we’ve finished with the basic principles, I would like to touch upon some principles that I’ve adapted from neuroscience to catapult my learning.

Some of these include nootropics and pharmacological agents, so I’ll add these at the end.